Wisconsin Expert Addresses State of the Grapes

As a result of the number of wineries in Wisconsin almost doubling in just the past several years, there has been an increased demand for wine grapes. Currently, all of the approximately 1,000 acres of cold hardy grapes being grown in Wisconsin are sold to winemakers.

At a recent meeting of the Wisconsin Vintner’s Association in Milwaukee, Dr. Dean Volenberg of the University of Wisconsin’s Door County Extension provided a status report on the wine grapes being grown by the University and commercial growers in the state.

(Volenberg, who has been at UW in Door County since 2006, was preceded by Dr. Richard Weidman, the former Superintendent of the Door County Peninsular Agricultural Research Station who retired in 2011 after 30 years of grape research.)

While 31 years of research is a nanosecond in viticulural terms, there is now a base of knowledge about grape growing in Wisconsin. During his presentation, Volenberg weighed the pros and cons of various cold hardy grapes and discussed their potential.

Marechal Foch– Foch is the grape Wisconsin has gone the farthest towards perfecting. Philippe Coquard at Wollersheim has been growing Foch for 30 years, and there are multiple wineries now making “elegant” Foch wines. This red wine grape is very winter hardy with low to moderate vigor and a distinct flavor. It’s also Wisconsin’s most widely planted grape.

St. Croix– This is Minnesota’s popular red grape, but it’s also common in Wisconsin. St. Croix is an early maturing grape that must be picked early or it will develop herbal notes. Because brix of 14-15 at harvest is normal, it’s not planted as often as other red wine grapes. A commercial grower on Washington Island (see map below) grows this grape for the specialty culinary market only and gets a higher price per ton than wine grape growers. (St. Croix can be used as an ingredient in sauce for stews.)

Frontenac– This variety has deeper, richer colors than most cold climate red grapes, is very cold hardy, and grows well in Wisconsin. Frontenac is a high acid grape, which is a problem. Used as a varietal red wine by only a handful of wineries, most Frontenac goes into port and dessert wines. It’s also a very high sugar grape with brix of 24-28 at full ripeness. However, there’s not much value added by picking above 23-24 brix.

To continue reading this post, you must either subscribe or login.[login_form][show_to accesslevel=”annual-membership” ]

Leon Millot– “Why isn’t this grape planted more in Wisconsin?” Volenberg asked. Leon Millot is very hardy and has a soft texture that’s nice on the palate. In the vineyard, it has a reputation for being susceptible to crown gaul, but it has survived in Door County for 20 years with no crown gaul. Leon Millot ripens earlier than the Foch, and the titratable acidity (TA) is in the 8 to 10 range which is lower than Foch.

(See related story: Top Tips for Controlling Crown Galln

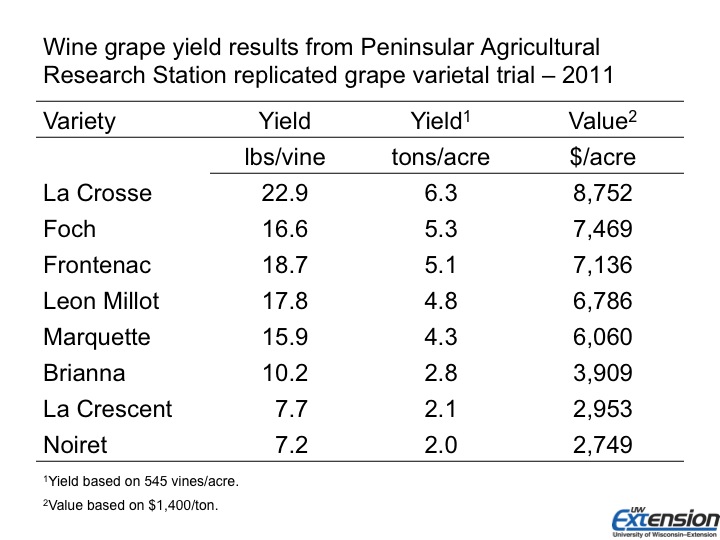

Marquette– This is the red wine grape winemakers are looking for. There is a Marquette shortage in Wisconsin currently, but it’s now widely planted, considering it was introduced as recently as 2006. Marquette can be tough to grow in Wisconsin Volenberg cautioned. It also has small clusters and low yields. Yields of 5-6 tons an acre from this grape are probably not achievable in Wisconsin. Growers need to get three acres per ton to make money at the current price of $1,400-$1,500 ton, he said. On the plus side, Marquette has high sugar and relatively low acid. The TA is around 15 when ripe. Marquette has good disease resistance and loose clusters.

Baltica– This is an Estonian grape growing at the Research Station in Door County. Volenberg said he likes Baltica because it ripens really early, around mid-August. The grape may be of less interest for southern Wisconsin, but it might be suitable for very cold locations. In a hot climate, it will produce a soft juice, but in a cold climate, Baltica can be made into a richer red wine. However, not much is known about yield currently as Baltica has only been in the ground a few years. Baltica also has a high grape seed oil content so it might have other applications.

Petite Pearl- This is another red wine grape to come out of Minnesota from breeder Tom Plocher. It has small clusters but lower acidity than Marquette. Petite Pearl is a grape that we’ll see planted more, Volenberg predicted. During 2012, it did well in areas where other grapes had frost damage because it stays dormant longer than most cold climate grapes. Overall, it also has higher tannin levels and lower TA than most red hybrids.

La Crescent– This white grape has complex flavors and intense aromas. It’s also high in acid and sugar. La Crescent matures late in September in Wisconsin. That’s an issue because grapes that have to stay longer in the field have more potential for some kind of disease, according to Volenberg. Late season bird damage is also a problem.

LaCrosse– This high quality white wine grape was developed by Elmer Swenson. It’s going into production heavily now because it’s a consistent producer in Wisconsin. Wollersheim uses it to make brandy also. The only drawback is that LaCrosse is susceptible to mildew and black rot.

St. Pepin- This is another white grape and a brother of LaCrosse. It’s not self pollinating so it’s planted with LaCrosse. St. Pepin is going into ice wine production because it can hang late in the year and it does not drop off.

Frontenac Gris– If you’re planting any type of Frontenac, Volenberg recommends planting it in the back of the vineyard because it’s susceptible to Phylloxera. While Phylloxera does not hurt vigorous vines like Frontenac, grape growers are tired of constantly explaining why their grape leaves are bumpy. Sustainable vineyards should use caution with copper sulfate around Frontenac. “Frontenac Gris has good tropical aromas and makes a great white wine,” Volenberg said.

Brianna- Elmer Swenson created this varietal but Ed Swanson in Nebraska named it. It’s the state grape of Nebraska with a pleasant floral nose. But if sugars are allowed to get too high, foxy notes will appear at around 18 brix. This is a good producer that’s making award-winning wines.

Minnesota 1220– This experimental grape is from the University of Minnesota, creators of Frontenac, La Crescent and Marquette. In Door County it’s producing quality fruit that makes a wine with spicy tones and a Riesling like quality. One of the drawbacks of 1220 is that the grapes hang tightly on the stems which may present challenges for crushing and destemming.

Publisher’s Note: Funding from grape industry research is in jeopardy in Wisconsin and other states. Pressure from the Door County Board of Supervisors and others was instrumental in continuing the critically important work of Dr. Volenberg and other dedicated researchers at the University of Wisconsin. On a less upbeat note, Becky Rochester’s contract with the Wisconsin Grape Growers Association will expire at the end of 2012 for lack of funding. Becky did exceptional work to promote and foster Wisconsin wine and she will be missed.

[wp_geo_map]

[/show_to][password-recovery-link text=’Lost Password? Click here for password recovery.’]

As I have stated before, anyone who is willing to pay 1400.00 per ton for anything grown in Wisconsin has either lost their minds or has no common sense regarding the market for fruit. At their best, hybrids when grown where they actually get ripe are worth maybe 500.00 to 700.00 per ton. Sorry to say that ain’t Wisconsin. Never will be unless global warming changes things.

An interesting article and Dean is to be complimented on his work. One note of disagreement is that although ‘Brianna’ has found favor with growerrs in Nebraska and quite a bit has been planted, it is not “the state grape of Nebraska”. If any grape could lay claim to that epithet, it would be ‘Edelweiss’, but actually, unlike Missouri (‘Norton’) and Indiana (‘Traminette’), Nebraska has not officially named a “state grape”.

Cheers,

Paul Read, University of Nebraska Viticulture Program

Mark

Excellent article on Dr. Volenberg’s important work. I am impressed that the data published here is from the Peninsular Experiment Station where the growing season is much cooler than most of the rest of the Midwest. If he can get that level of ripening at that site there is hope that ripening in much of the rest of the region willl be well within necessary parameters. Also impressed that Dr. Vollenberg was not shy about describing unique wines made from these Midwestern grapes. In my view this is an advantage we have over more established wine regions. Dragging out another tired old Cabernet or Chardonnay and trying to pass this one off as “high quality” is a problem we don’t have. Our grapes are unique and the wines are also. We should emphacize our uniqueness as the public loves it and buys them. These grapes are our strength, not our weakness.