Using Enological Tannin Additions to Enhance Red Wine Structure and Mouthfeel

By Stephanie Groves, Midwest Grape and Wine Industry Institute, Iowa State University

This article originally appeared in the February 2014 issue of Northern Grapes News, a publication of the Northern Grapes Project.

This article originally appeared in the February 2014 issue of Northern Grapes News, a publication of the Northern Grapes Project.

Tannins are important to the quality of red wines, particularly to the color stability and the structure (body and mouthfeel) of the wine. They are also involved in complex wine aging reactions and thus are important to the aging potential of red wines. The source of tannins in wine is numerous, as they can come from the grapes themselves (skin, seeds, and stems) and/or the barrels the wines are aged in. Tannins and their extraction, and proper integration, are essential to making a premium red wine.

Enological Tannins. Typically, cold-hardy cultivars have low tannin levels even when enological techniques and practices are used to maximize tannin extraction.Thus, winemakers may still fall short of making premium fuller-body red wines with color stability and long aging potential. Enological tannins are “commercial tannins produced by extraction of tannin from oak, chestnut, or birch woods and other suitable plant sources, including grape seeds.” [Jancis Robinson, The Oxford Companion to Wine]. These powders can be added as treatments during the winemaking process, and have become a popular way to increase tannin levels in wine.

Jessamy Adams, left, and Tammi Martin of the Midwest Grape and Wine Industry Institute at Iowa State University assist with the tannin addition trials that conducted at Tassel Ridge Winery.

This study was undertaken to evaluate the effects of tannin additions on the phenolic composition and mouthfeel improvements of Marquette and Frontenac wines.

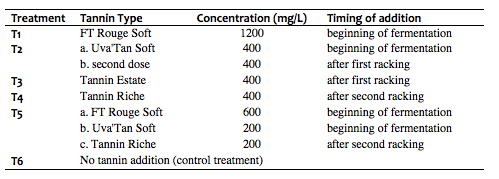

Enological Tannin Additions. As part of the Northern Grapes Project, the Midwest Grape and Wine Industry Institute conducted enological tannin addition trials in Marquette and Frontenac wines. Tassel Ridge Winery (Oskaloosa, IA) graciously provided grapes and space for the experiments. We investigated five tannin treatments (T1-T5) using four different commercial tannin products, added alone and in combination, at different times and in varying amounts (Table 1). Treatments were compared to the control (T6). The four tannins used fall into the categories of fermentation (FT Rouge Soft and Uva’Tan Soft), cellaring (Tannin Estate and Uva’Tan Soft), and finishing (Tannin Riche) tannins, which refers to when the tannin additions are made during the winemaking process.

Results: Wine Chemistry. The tannin additions do not appear to have an effect on pH, titratable acidity, volatile acidity, residual sugars, and alcohol between treatments for each wine type. These results indicate that enological tannin additions have little to no effect on yeast performance and the basic chemical properties of the wines.

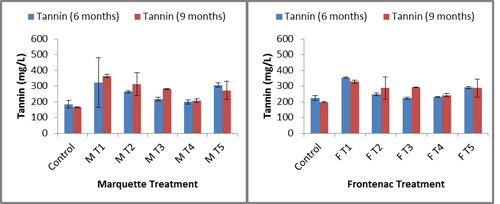

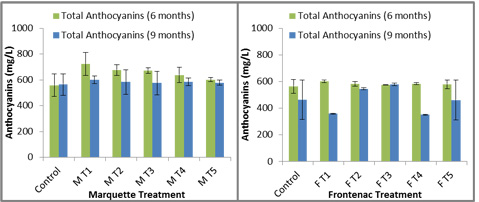

Results: Phenolic Profile. Wines were analyzed for phenolic content after six and nine months of aging. At six months, the main results observed between the control and the various tannin addition treatments in Marquette and Frontenac were an overall increase in the concentration of tannins compared to the control (Figure 1). As expected, those wines that received the highest concentration of tannin additions (T1 and T5) had the greatest concentration of quantifiable tannins. The other difference in the phenolic profile of these wines can be observed by measuring the total anthocyanin concentration (Figure 2). Statistical analysis of this data (one-way ANOVA) revealed that in young Marquette wines (6 months), there was no statistically significant difference in tannin or anthocyanin content between the treatments. Even though the difference observed between the raw numbers was not mathematically significant, it could still affect the sensory characteristics of the wines. There was no increase in anthocyanin levels in the young Frontenac wine.

Figure 1. Tannins in young wines (6 months old) and aged wines (9 months old) treated with enological tannins. Values reported as mean concentration (mg/L) of each compound (n=2).

Figure 2. Total anthocyanins in young wines (6 months old) and aged wines (9 months old) treated with enological tannins. Values reported as mean concentration (mg/L) of each compound (n=2).

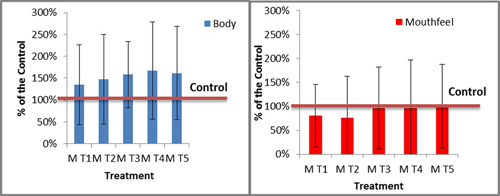

Figure 3. The effect of enological tannin additions on sensory perception of body (thin to full) and mouthfeel (harsh to soft) of wine made from Marquette grapes. The treated wines were both fuller and harsher compared to the control. In an informal survey, treatment four was the preferred treatment.

The phenolic profile was measured again after nine months of aging. Compared to the samples taken at six months, a similar trend in the phenolic profiles was observed for tannins and total anthocyanin concentration (Figures 1 and 2). At nine months, a significant difference in the tannin levels was observed between treatments for the Marquette wine (p > 0.05). This may indicate that the tannin levels are increasing with age depending on the treatment, as observed in treatments M T1, M T2, M T3, and M T4 (Figure 1). The decrease in total anthocyanins, in both Frontenac and Marquette, observed at nine months may be a result of the formation of complexes with other phenolic compounds or oxidation reactions.

Results: Industry Evaluation. The young Marquette wines underwent sensory evaluation to determine the effects of tannin additions on body (thin to full) and mouthfeel (harsh to soft). The panelist were untrained industry members that were asked to rate the wines on a scale of 1-5 (1 being thin and 5 being full; 1 being harsh and 5 being soft). The overall trend of the sensory analysis showed that for all treatments the tannin additions lead to a fuller body wine (Figure 3). However, due to lack of aging and integration of the tannins, all of the treated wines were rated as harsher than the control. It is expected that this effect should soften with time. We will be taking another phenolic profile measurement at 18 months and preforming another industry tasting to verify these results. In terms of preference, the industry panel preferred treatment 4 (Tannin Riche) to the control and the other treatments. Tannin Riche is derived from 100% toasted French oak.

Members of the Iowa wine industry at the annual Iowa Wine Growers Association meeting in March 2013 participate in a tasting and evaluation of Marquette wines treated with enological tannins.

Conclusions: In our tannin trials, the addition of enological tannins at different levels and times during the fermentation in Marquette and Frontenac wines was evaluated. Phenolic profiles for all treatments showed slight variations in the levels of tannins and total anthocyanins. The wine’s chemical properties (alcohol, pH, titratable acidity, volatile acidity and total SO2) were not impacted by the additions, indicating they have little if any effect on the fermentation kinetics. An industry tasting of treated Marquette wines indicated that the additions for all treatments resulted in a fuller bodied wine. If a winemaker wishes to employ enological tannin additions to make premium red wines, they should work closely with the supplier to determine which type or combination of tannins and the timing of the additions that will work best for their application.

The Northern Grapes Project is funded by the USDA’s Specialty Crops Research Initiative Program of the National Institute for Food and Agriculture, Project #2011-51181-30850