Cab Dore’ Combines Best of Old and New Worlds

Homepage photo: Joseph and Lucian Dressel

When you read all the old grape breeding literature from John Adlum to George Hussmann to U.P. Hedrick to Philip Wagner, the one common theme is the endless search for high quality wine grapes that will grow in the East. Wagner, as the promoter and propagator of the French Hybrids, is really the founder of the modern Eastern wine industry, yet even he states in his books that none of the Hybrids measure up to the best wine grapes of the world.

The reason for this is simple genetics. The American vine parents used by the French to create hybrids were not used as wine grapes in America. The French grapes used as parents were grapes grown for the mass production of low quality bulk wine. No amount of inbreeding could overcome those handicaps.

When we started grape breeding in the late 1990s, the literature almost universally had Cabernet Dore’s parent, Norton, as being a 100% Vitis Aestivalis. (Some still like to claim that Norton is the “All American Wine Grape.”) We, on the other hand, maintained that Norton was 50% Vitis Vinifera and 50% Vitis Cinerea.

We derived that conclusion from reading Thomas Munson who noted that he had never seen an hermaphroditic wild American grape vine; all were either males or females; none had perfect flowers. Munson also noted, during his 50,000 miles of traveling the grape forest primeval in the 19th Century, that he had only once come across a white wild vine out of the tens of thousands that he observed and collected.

Munson noted that one-third of Norton’s seeds came up as white grapes, and it’s obvious that it has perfect flowers, so to us, it had to be half Vinifera.

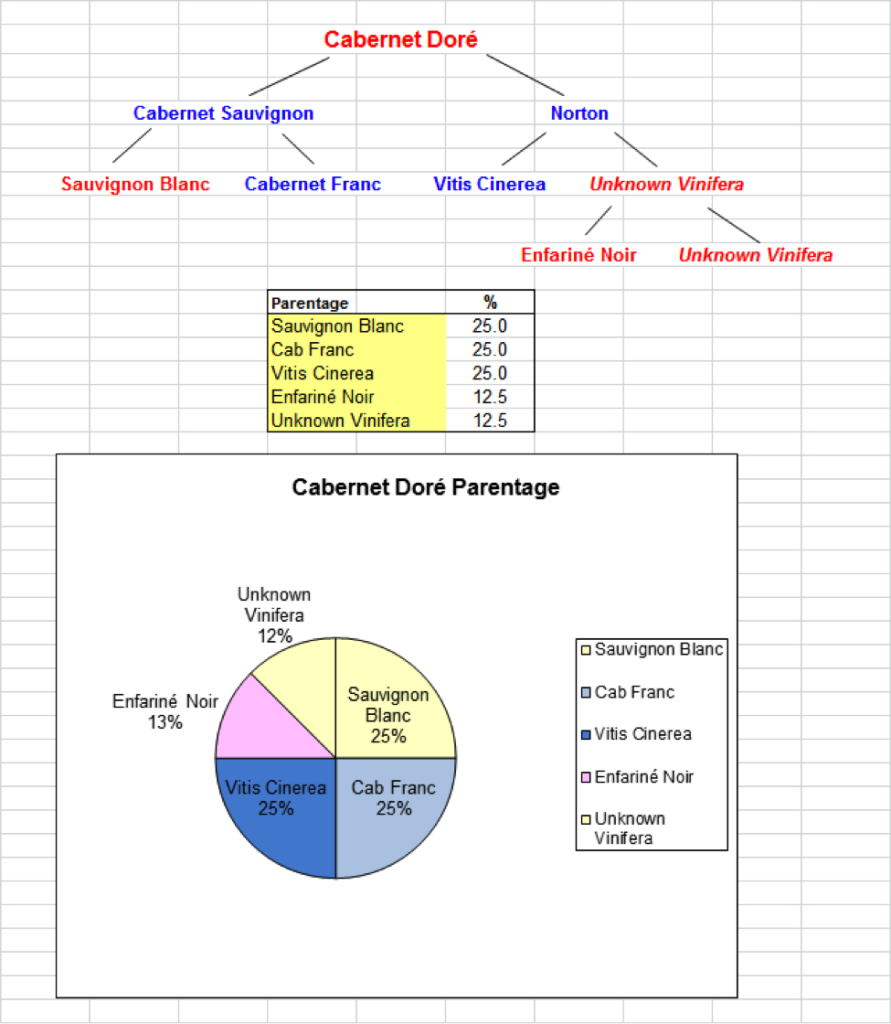

All of our conclusions were verified when Gerald Dangl at UC Davis, et. al, did extensive DNA research. He also turned up Enfarine’ Noir as a grandparent, so this rather long story is an explanation of where that ancestor of Cabernet Dore’ came from. Incidentally, Enfarine’ Noir seems to be closely related to Gouais Blanc which has turned up as the parent of a host of excellent Vinifera including Chardonnay.

A parentage chart for Cabernet Dore’ appears at the bottom of this article. I also highly recommend Dangl’s article about the origins of the Norton grape. DNA testing is a wonderful thing.

With the Davis Viticultural Research vines, the concept is, “Why not start with the best American wine grape and breed it with the best wine grape in the world, Cabernet Sauvignon?” This was not easy or quick. In the end it involved a lot of luck, but Cabernet Dore’ was one of the happy results.

I am often asked how can one get a white grape out of two black grapes? The answer is, of course, that both Cabernet Sauvignon, and (very likely) Norton, have one white parent each, so it is naturally that some of the offspring would be white. Which brings us to Cabernet Dore’.

Cabernet Dore’ is like the grandchild that turns out to be the spitting image of one of its grandparents, in this case Sauvignon Blanc (I don’t want to digress, but in breeding, the parents are really the conduits through which the genes of the grandparents flow and recombine, which I think is one reason that kids and grandparents seem to often get along better than parents with their own kids.)

Cabernet Dore’s fruit, canes, leaves and growing habits (very upright) are virtually identical to Sauvignon Blanc. The wine itself is like a tamed down Sauvignon Blanc with all of the nice muscat -like characteristics but none in excess.

Fortunately however, Cabernet Dore’ has also inherited the cold resistance and disease resistance of Norton. It grows on its own roots, so it is phylloxera resistant. We have never seen crown gall, even in very poor locations. We have also never seen powdery mildew and only a rare spot of black rot. Under the worst of conditions, when one grower stopped spraying for six weeks during a wet summer we saw some downy mildew, as we also did on Norton. This was quickly stopped when spraying continued.

Cabernet Dore’s upright growth habits make it ideal for VSP trellising. It should be planted 10 feet apart in the rows and 8 to 9 feet apart between vines. It is vigorous, but the growth is not rampant, as can be the case with Norton.

To sum up, what are the most important reasons for growing Cabernet Dore’?

First and foremost is to have healthy, hardy vines. If you don’t start with that, nothing else matters. Next is wine quality. Cabernet Dore’s superior breeding gives its wines the ability to compete with the best of California and Europe.

Like its parent Cabernet Sauvignon, the wine from each vineyard and winery highly reflects the regional differences of terroir and management. A Kentucky Cabernet Dore’ is different from an Arizona Cabernet Dore’, and that’s a great part of the fun of doing this. Each grower and winemaker is in effect crafting his own world-class wine. The chance to do that is why I think most people get into this business in the first place. I think it is one of the finest white wine grapes in the world for dry white wine.

Lucian Dressel is the founder of Davis Viticultural Research in California. Dressel also founded Mount Pleasant Winery in Missouri during the 1960’s and obtained the first approval in the United States for an American Viticultural Area which became known as the Augusta Appellation.

See related story: Dr. Norton Had a Baby and Named Him Crimson Cabernet

Lucian,

I enjoyed the article. I was curious of the basis for your claim that the wild species in Norton, and hence Cabernet Dore, is Vitis cinerea. You mention the earlier claims that Norton was 100% Vitis aestivalis, those claims are erroneous for the reasons you cite. But every paper I have seen does put the wild background in Norton down to V. aestivalis at between 25-75% (probably 50%), and not Vitis cinerea. This includes the Dangl et al. paper you reference – http://naldc.nal.usda.gov/download/41645/PDF

Mark,

Thanks. Excellent question. When I spoke to Dangl after he wrote the paper he said that the DNA evidence could not rule out either wild species as a parent.

The most convincing evidence for deciding the American parentage of Norton, whether Aestivalis or Cinerea, is found in Pierre Galet’s “Precis d’ampelographie pratique” (translated by Lucie Morton, published in English in 1979). Galet, who I think everyone will concede was the greatest ampelographer of the 20th Century, states on page 142, that … “V. Aestivlis is of no interest as a rootstock because its resistance to phylloxera is only fair (9/20).” “No interest as a rootstock”, Wow!! Norton, on the other hand is one of the most phylloxera resistant of all commercial vines. Since one of Norton’s parents is a Vinifera, with zero resistance to phylloxera, then its American parent would have had to have been a doozy when it came to phylloxera resistance. Aestivalis apparently has barely enough resistance to protect itself, much less impart a large dose of resistance to its offspring. V. Cinerea, on the other hand is described by Galet (page 146) as having “… good resistance to phyloxera…” This, I think, is the most telling piece of evidence.

In addition, Galet also states that Aestivalis has an “unpleasant flavor’ whereas Cinerea has an “acid flavor”. One of Norton’s great virtues is that it lacks the unpleasant wild flavors that plague the other native varieties (although its acid flavor is famous). If Aestivalis were Norton’s American parent, it is almost certain that the some of Aestivalis’s unpleasant flavors would have been imparted to Norton. Every grape that was ever crossed with a Labrusca, for instance, retains some of that unique and unmistakable flavor. Norton’s flavor is rather neutral, with no wild flavors, which is one of the many reasons why we chose it as the American parent for all the DVR varieties. Aestivalis and Cinerea look a lot alike in many ways, and it wasn’t until Engelman reclassified them as separate species in 1883 that their distinct differences were noted. By then, the Aestivalis heritage story for Norton was ubiquitous and highly resistant to change until DNA evidence and Galet came along to indicate otherwise.

Lucian,

Thanks for the article and comment. I am really excited to try some of your grapes, including Cabernet Dore’.

I think I should point out that there are V. aestivalis accessions with very good phylloxera resistance, so I don’t think that argument supports a V. cinerea background for Norton any more than the SSR data does. See Grzegorczyk & Walker, 1998:

http://ajevonline.org/content/49/1/17.abstract

All the data I’ve seen, whether DNA or ampelographic, strongly suggests V. aestivalis was Norton’s wild parent.

Jon,

Thanks. You raise a very important point. All individual wild grape vines came up from a seed and are the product of sexual reproduction so each vine is unique. They also interbreed like alley cats. When we classify them into “species” it’s like classifying people into “races”. It’s often not that clear where an individual belongs. The vine that Pierre Galet is calling Aestivalis has insufficient phyloxera resistance to make it the logical choice for a parent of Norton. Also the unpleasant flavors of Aestivalis are nowhere to be found in Norton or its offspring.

Either Galet has a vine that is not a typical Aestivalis, or the vines that Grzegorczyk et. al. are calling Aestivalis would be classified by Galet as something else. Who knows? One thing, I think, is certain. The individual vine that was Norton’s parent (circa 1820?) is extinct. We can be thankful that before it was grubbed up by some Virginia farmer it passed on its phyloxera resistance and neutral flavor to Norton, which is truly one of a kind.

Lucian,

Thanks for your reply. I agree; the lines between Vitis species are sometimes blurred, and there has to be natural hybridization taking place.

I would bet that what Galet and Walker’s lab had were both aestivalis. For a lot of traits, like phylloxera resistance, there is considerable variation within a given species. I’m sure there are aestivalis specimens spanning a wide spectrum of resistance. The same is true for traits like fruit chemistry, flavor/aroma, and fungal disease resistance.

-Jon

What yeast reccommendations for this grape?