Joe Mills on Wine and Poetry

Joseph Robert Mills, poet, essayist, dramatist, critic, has the credentials of a professor whom you might expect to find nibbling at cheeses and sniffing wine at the faculty club. Growing up in Indiana, he left after high school to gather an undergraduate degree from the University of Chicago and graduate degrees from the University of New Mexico and the University of California-Davis. He now lives in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, where he holds the Susan Burress Wall Distinguished Professorship in the Humanities at the University of North Carolina School of the Arts.

Joseph Robert Mills, poet, essayist, dramatist, critic, has the credentials of a professor whom you might expect to find nibbling at cheeses and sniffing wine at the faculty club. Growing up in Indiana, he left after high school to gather an undergraduate degree from the University of Chicago and graduate degrees from the University of New Mexico and the University of California-Davis. He now lives in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, where he holds the Susan Burress Wall Distinguished Professorship in the Humanities at the University of North Carolina School of the Arts.

So why publish a story in Midwest Wine Press about a North Carolina academic who admits to having sampled only beer in his youth in the Midwest during the Eighties? (Oh, yes, he mentions that an older sister mixed lambrusco and 7-Up in a cooler long before Bartles and James made a fortune with a similar concoction.) And in Chicago at college he became interested in wine first, as he says, ‘because it seemed adult and sophisticated, two things I desperately wanted to be,” and second, because it was served free at a lot of parties.

Well, Joe Mills admits now to being an oenophile, though not, he declares, a connoisseur. Broadly, that means that he finds that wine is a pleasurable way of getting to know people and places. He rarely has a glass of wine alone. ‘Whenever I picture a wine image, there are always two glasses, never one,” he says. And he especially likes conversations with wine growers and vintners. As he explains, ‘I love to talk to people who make things and to have discussions about craft.”

With his wife Danielle Tarmey, Mills wrote A Guide to North Carolina’s Wineries, published in 2003 when there were but twenty-four wineries in the state. When the second edition came out in 2007, there were sixty-four. With both editions, Joe and Danielle, then without children, visited every winery, conversing with wine makers for as long as four hours at each site. Now with young children, they know that pace would be daunting, particularly since the number of wineries in North Carolina is estimated at one hundred, some of them, no doubt, encouraged by the focus Joe and Danielle’s book has brought to the industry.

The research Mills and Danielle did on that guide helped inform Joe’s book Angels, Thieves, and Winemakers, poems about wine, grape growers and vintners, and, of course, drinkers. Joe, who has written three books of poetry and teaches creative writing, says, ‘One of the things I love about the wine industry is the language — angel’s share, thief, jeroboam. That language is metaphorical, and people’s experience with wine is as well. In other words, the drinking, tasting, engaging with wine often isn’t about the wine itself, but usually something else. Wine is a beverage, a food if you prefer, but it’s also a symbol. So it’s a chance to examine human relationships.”

Joe’s take on wine echoes that of Benjamin Franklin, from whose writing he chooses this well-known epigraph for his book of poetry: ‘Behold the rain which descends from heaven upon our vineyards, and which incorporates itself with the grapes, to be changed into wine; a constant proof that God loves us, and loves to see us happy.” And happy is the reader who can settle down with these poems, a friend, and a good bottle of chamborcin, the product of a grape that is enhanced by the soils and climate of Missouri, Illinois, Kentucky, Indiana, and, yes, North Carolina.

James Ballowe, Distinguished Professor Emeritus of English, Bradley University, grew up in the wine-growing region of Southern Illinois. He now lives in Ottawa, Illinois, which has just hosted a successful Illinois wine festival. His latest books are A Man of Salt and Trees: The Life of Joy Morton, Northern Illinois University Press, and an anthology, Christmas in Illinois (University of Illinois Press).

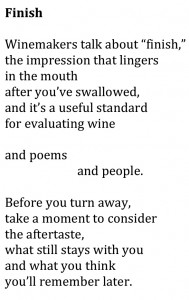

A poem from Mills’ book, Angels, Thieves and Winemakers

Standing in a Vineyard with a Winemaker

Who Explains Some Reservations He

Wishes Were More Widely Shared

A grape should be

difficult to crush.

Not physically, of course,

any more than it’s hard

to break an egg

or smash a pumpkin,

but you should always

hesitate to rupture

a container

that gives coherence

to chaos,

especially one

holding so much

juice and flesh.

And consider

the shape:

a sphere, a circle

an orb, a globe,

the same as the planets,

the moon, the stars.

Since this is the form

the universe wants

material to take,

shouldn’t we be careful

before destroying it

in the hubris

of thinking

we can make

something better?