Avoiding Stuck Fermentation

Perhaps you have come across the diligent winemaker. Everyday he records the density of fermenting musts in a notebook and plots the data on graph paper. This careful winemaker also tracks the rate of fermentation, keeping an eye out for the dreaded stuck fermentation.

Yet our meticulous winemaker rises one morning to find fermentation has stopped. In a mild panic, the winemaker goes immediately to yeast supplier websites looking for solutions. The stuck wine will also have to undergo malolactic fermentation so the situation could be critical.

This is a situation that no winemaker wants to be in. So Instead of focusing on dealing with the aftermath, this discussion will focus on understanding ways to avoid stuck ferments. First, however, it helps to review the negative outcomes of stuck fermentations and the processes that control them.

Stuck ferments can cause many problems. Most notably is a must with unwanted residual sugar. For dry wine or malolactic production this is particularly difficult. Bacteria can consume the excess sugar resulting in increased volatile acidity. Sluggish, slow or stressed ferments can produce aromas that include rotten eggs, nail polish remover and vinegar. Furthermore, as wine is coerced through fermentation, there is increased opportunity for oxygen exposure and oxidized aromas like acetaldehyde. Acetaldehyde is also a byproduct of stressed yeasts.

Alcoholic fermentation is a complex process. A long list of factors and variables can impact the final outcome. Potential sources of problematic fermentations are:

• Improper nutrition

• Brix and Ethanol content

• Yeast selection

• Competition from other organisms

• SO2

• Temperature

• Yeast rehydration

• Juice clarification

One of the biggest factors in preventing stuck fermentations is providing the yeast with appropriate nutrition. Determining yeast assimilable nitrogen (YAN) is accomplished by measuring free amino acids and ammonia. Each yeast company and distributor has nutrition protocols on what type of nitrogen products to use and when to use them.

To continue reading this post, you must either subscribe or login.[login_form][show_to accesslevel=”annual-membership” ]

The biggest challenge for wineries is not understanding how to use yeast nutrients, but knowing how much to use. Many small wineries lack the ability to accurately and quickly measure the starting YAN concentration in their must. Without knowing the starting YAN, everything is a guess. In many cases, hybrid grapes are excessive in nitrogen. However, at the end of the day, finding a solution to measuring nitrogen content in the must remains a priority for small wineries.

Aside from nutrition, osmotic pressure from the initial sugar concentration of the must and the resulting ethanol content has a major impact on yeast. In an effort to reduce acidity, many wineries will let fruit hang late into the season. An unwanted side effect of that strategy is high sugar content. Certain varieties are more prone to excess sugar than others. Most notable are Marquette and the Frontenac varietals.

Dealing with elevated starting brix requires greater nutritional care. If the potential alcohol is over 14%, or even 15%, dilution is worth considering. Also, remember to choose an appropriate strain of yeast that can handle high alcohol wines.

Prevention of a stuck fermentation requires using yeast with the appropriate metabolic capacity to fit the situation. High brix wines require yeasts that have higher osmotic tolerance.

Yeast should also be fresh and properly stored. Old yeast or yeast that has been subject to high heat or humid conditions should be discarded.

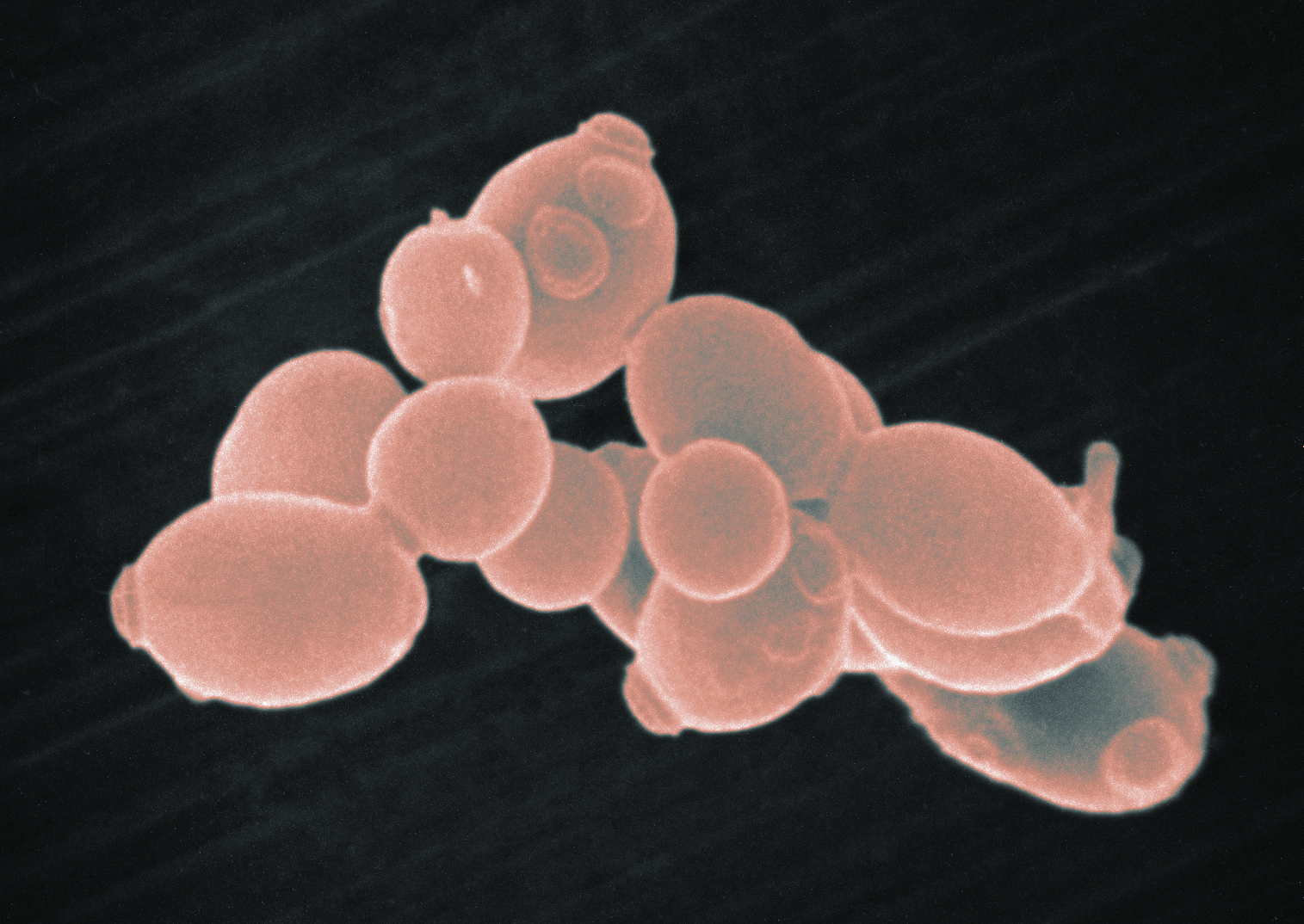

Competition from spoilage yeasts, molds and bacteria can encourage stuck fermentations. These spoilage organisms consume needed nutrients and produce competitive compounds to inhibit the yeast. To avoid microbial contamination, use clean fruit and avoid delays in inoculating musts.

Many of the varietals picked in Minnesota have low pH values. Here, pH’s between 2.9 and 3.2 are common. At these low pH’s, a little sulfur goes a long way. Yeasts do have the ability to handle SO2 in wine, but excessive levels can be problematic. If the fruit quality is high, use values around 0.8 molecular.

Both high and low temperatures can impact yeast fermentation. Very cool temperatures will result in slow fermentation. In many cases that is desirable. What we want to avoid however, is very slow fermentations, particularly if dry wine is desired. Conversely, very hot fermentations can damage the yeast. Large fermentations without temperature control can get out of hand quickly with temperatures approaching 90F or higher. Yeasts are small creatures where small changes in temperature can greatly affect them.

Follow the recommended yeast hydration protocols from the suppliers very carefully. A significant issue is slowly lowering the hydration temperature from the 40C (104F) down to must temperature. Failure to properly acclimate the yeast can shock them, killing many of the cells or resulting in mutant cells. Either the starting inoculation rate will be too small to support a long fermentation, or the cells that survive are not strong enough to handle the ethanol stress later in fermentation.

Also pay attention to using the appropriate amount of yeast. A high enough yeast cell concentration is required at pitching to avoid fermentation problems later.

In winemaking, white musts are settled to remove excess sediment and berry particles. Too much dissolved material may lead to off flavor production. Too little dissolved material can stress yeast as they use the material in the juice to distribute themselves throughout the must. Yeast added to over-clarified must can quickly settle to the bottom of the tank where reductive aromas can propagate. Wineries with centrifuges or turbidity meters can measure the level of clarification in the juice and rack according to the yeast manufacturer’s recommendations. Wineries lacking these techniques should avoid excessive clarification of the must. Rack off the large heavy lees that settle quickly after pressing, but try to rack some of the lighter lees that settle on top of the lees layer. Lallemand recommends using chitin to provide suspended material in over clarified musts.

Understanding the factors contributing to stuck or sluggish fermentations prevents problems later. Providing yeast with the appropriate environment helps ensure a positive and desired outcome. As with any wine fault, prevention is easier than fixing the problem once it occurs.

[/show_to][password-recovery-link text=’Lost Password? Click here for password recovery.’]

[wp_geo_map]