Monitoring SO2 in the Winery

Wine, all on its own, is a fairly good antiseptic. The tartaric acid in wines made from grapes is a relatively strong organic acid that helps keep the pH of the wines low, which in itself is a good way to inhibit microbes (not much survives below pH 3.4).

Add to that the antimicrobial properties of alcohol, and you have a beverage that could help you survive through a plague. However, that’s not to say that NOTHING will survive in wine. Acetic Acid bacteria, Brettanomyces, and other spoilage organisms can literally turn a wine sour and make it generally unpleasant to drink.

This is where the use of sulfur dioxide (SO2) in the winery is imperative. In addition to antimicrobial properties, SO2 is also an antioxidant and antioxidasic. It is arguably the most important additive in wines, and except for alcohol, is the only component in wine that requires a warning statement on the label. Thus, it is important that wineries not only ensure that they are correctly dosing and monitoring their wines with SO2, they also need to ensure that they are properly measuring it as well.

Using SO2 in the winery. Sulfur dioxide is a pretty noxious gas, and is not typically used in its pure form in small wineries. Most often, wineries employ it by adding a potassium salt of sulfurous acid, known as potassium metabisulfite (KMBS). It is important to understand that by weight, KMBS is about 57% sulfur dioxide. Thus, for every 100 grams of KMBS added to a wine, 57 grams of SO2 is added. To complicate matters, the majority of that 57 grams of SO2 becomes chemically bound to certain compounds in wine when it is first added, rendering it useless to protect the wine!

SO2 Binding in wine and why we want it free! Any compound in wine with a carbonyl function will bind sulfur dioxide. While many of you have no idea what that means, just know that there are many compounds in wine that have a carbonyl group. Glucose, acetoin, diacetyl, galacturonic, α-ketoglutaric and pyruvic acids, and acetaldehyde are all compounds that will bind SO2. This effectively does exactly what it sounds like: it ‘ties the hands” of sulfur so that it is unable to do its job! The good thing to know is that once all the binding sites are filled with sulfur, the remaining sulfur is floating around in the wine, free to do its job!

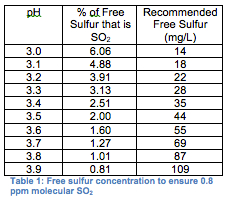

The term ‘free sulfur” is used to describe the unbound or ‘working” portion of sulfur in wine. In reality, only a small percentage of your free sulfur is actually ‘working” against microbes, and this working portion depends on a wine’s pH. At a lower pH, more of the free sulfur is in the SO2 form, while at a higher pH, more of it is in the form of bisulfite (H2SO3-), which is essentially ineffective in wine (see table 1).

Adding and monitoring Sulfur in wine. To follow good winemaking practices, there are three critical times when a winemaker should think about sulfur addition: at crush, following the completion of alcoholic fermentation or malolactic fermentation, and any time a wine is moved (exposed to oxygen). In unfermented juice or must, a small amount of added sulfur will help kill spoilage bacteria and provide some protection from oxidation. Generally, 30 mg/L of total sulfur is sufficient to halt bacterial problems without hindering fermentation in low pH wines from quality fruit (absence of rot). Following fermentation, the quantity of sulfur to add is not quite as formulaic.

A dry wine should contain enough free sulfur to ensure that the molecular SO2 concentration is at least 0.8 mg/L, while sweet wines should be maintained with higher free sulfur concentration (1.5 mg/L molecular SO2). Of course, these recommended levels can also vary depending on which book you read. The initial sulfur addition following fermentation needs to be higher to account for the fact that much of what is added at this point will become bound to sugar, acetaldehyde, and other compounds in the wine. Often adding more sulfur during the initial dose following fermentation will help keep the overall additions lower. Once all the binding sites have been filled, any added sulfur will increase the free sulfur concentration proportionate to the amount added.

How much sulfur should I add? Free and total SO2 measurements can be tricky and time consuming, so it is often tempting to simply come up with a standard addition and rely on guesses to ensure that the proper amount was added to the wine.

Without measuring, however, you have no idea if you’ve added too little, too much, or just the right amount. Ideally, the free and total sulfur should be measured before and after any addition, and adjustments should be made to make sure that the free sulfur follows the guidelines in table 1.

After fermentation and racking wine off lees, wine becomes susceptible to oxygen exposure. The oxidation of ethanol to acetaldehyde is the most noticeable result of oxygen exposure. This compound gives wines an apple or nutty aroma, and will mask fruity and floral aromas.

Any time a wine is racked or pumped, there is some oxygen exposure that can result in the formation of acetaldehyde that will bind a portion of the free sulfur. One can expect to lose 10-20 ppm of free sulfur any time a wine is moved.

Winemakers should be measuring the free sulfur before and after moving a wine, and accounting for this loss in SO2. This becomes trickier during bottling, as it impossible to adjust the free sulfur once it is bottled! Measuring the free sulfur on wines before and after bottling can help winemakers predict the expected loss of free sulfur, and ensure that additional sulfur is added prior to bottling to make up for this expected loss.

Wine storage post-fermentation. Containers that are used to store wine need to be topped up to prevent oxygen exposure and the formation of Acetaldehyde. Plastic (polypropylene and polyethylene) tanks are somewhat permeable to oxygen, as are variable height tanks (along the inflatable rubber gasket). Some of the fermentation locks used by winemakers may not be suitable for post-alcoholic fermentation storage, either.

Any lock which does not create a tight seal (e.g., spring loaded rubber seal with over-pressure protection) or barrier (e.g., traditional liquid filled fermentation lock) will allow oxygen exposure. Thus, over long-term storage, it is important to measure free sulfur on a monthly or quarterly basis, depending on the type of storage container used.

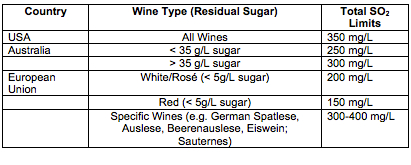

Legal Limits for SO2. Unfortunately, SO2 is an irritant and can have some serious side effects for consumers who are sensitive. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration estimates that one out of 100 people has an increased sensitivity to sulfites, which can cause an array of symptoms of varying severity from skin reactions to gastroenterological problems and pulmonary distress. For this reason, wines with added sulfites need to be labeled as such, and the FDA limits the maximum amounts that can be added to wine. These are limits for total sulfur, or the bound and unbound portion of sulfur in the wine. It is easy to see how high pH and sweet wines might easily exceed this limit if a winemaker is not carefully monitoring and adding sulfur.

Katie Cook is the enology project leader in the Department of Horticultural Science at the University of Minnesota. She grew up in Prior Lake, MN, but has worked and studied in France, California and Argentina.

This article first appeared in “Notes from the North” which is published by The Minnesota Grape Growers Association and is reprinted with permission. For more information about the MGGA see: Minnesota Grape Growers Association