Glass Wine Bottles Still Favored by Consumers

New wine packaging methods have become more common in the past several years, but the fact remains that most wine is sold in standard 750 ml bottles. How many bottles of wine are sold in a year in the United States each year? No one is exactly sure, but the number of wine bottles produced nationally each year is probably over 4 billion.

‘Glass wine bottles are still the most popular choice for winemakers, for both their ability to preserve the aromas and tastes of wines and by contributing to the consumer’s perception of a quality product inside the bottle,” said Andrew Bottene, vice president at TricorBraun WinePak, the largest distributor of wine bottles in North America.

TicorBraun recently took me on a firsthand tour of a glass factory to get an insider’s perspective on how wine bottles are made.

All glass factories run 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Glass is created from raw materials, such as limestone, soda ash, sand, and cullet, which is recycled glass from both within the plant and post-consumer glass.

Recycled glass saves both on raw materials and energy. Some glass factories now use up to 70% recycled materials, especially in states where glass bottles have a deposit fee required by law. Michigan’s $.10 bottle deposit rate is the highest in the U.S. and 95 % of Michigan bottles are returned for recycling. Since glass is 100% recyclable, there is little likelihood that plastic will be a viable replacement anytime soon.

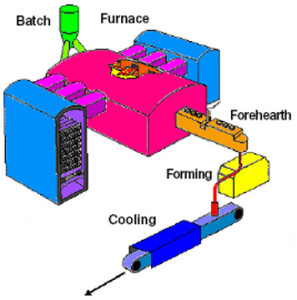

Back to the manufacturing process. Once materials are weighed and mixed, they enter the furnace, where glass temperatures can reach between 2,100-2,800 degrees. Inside the furnace, the glass must be kept on a very consistent level, which means a tolerance within 1/100th of an inch. This keeps the glass homogeneous, the key to a quality glass bottle.

Next, the melted glass, which looks like bright orange lava, goes into a forehearth and then a forming machine to create the shape of the wine bottle. Each wine bottle has its own specific mold (think of it as a mold you use for cooking cookie shapes) and if the bottle size or shape changes, the entire line has to be shut down to change out the molds.

Once the formed glass bottles leave the mold at temperatures around 850 degrees, they move down the line to receive a special hot end coating. The bottles next go into the annealing lehr, a very large kiln, to reheat the glass to 1,150 degrees and then the bottles gradually cool. This process reduces stress on the containers and naturally strengthens the glass.

Next, the bottles go to a cold end coater, which adds a coating so they do not scrape each other. If scraping occurs, the bottles become slightly roughened. This could make the bottles ‘walk up” on each other during the filling line process, which gums up the works.

Finally, the bottles enter a final fast cooling section to bring the temperature down to 100 degrees.

Following manufacturing, glass bottles go through a series of tests. (Think of it as the Crossfit for bottles.) The bottles are first put through a pressure roller to test for breakage. The thickness of the glass is measured and the opening of the bottle is checked to be level and of an exact diameter.

A series of cameras inspect for minor visual irregularities, which can include iridescent, scratches and blemishes. If the imperfections were allowed through the line, the scratched bottles are more likely to break during filling or distribution.

Each bottle is also stamped or printed on the bottom with a series of numbers or letters. If any bottle is returned due to irregularities, the factory will know exactly which line it ran on and what batch it was from.

Larry Petraitis, the vice president of Global Glass Supply for TricorBraun, says, ‘Since so much emphasis is spent on looking at packaging in the wine industry, wine bottles must have a lower level of imperfections than other glass in the beverage industry.”

Illustration created by Packaging-Gateway.com

After label, capsule, cork, and of course wine, are added, a quality wine bottle is a work or art. Wine consumers are more apt to display their favorite wine bottles than a glass jar of pasta sauce or pickles. Creative uses for wine bottles include candle holders, soap dispensers, wind chimes, tiki-lamps and bird feeders. Cobalt bottle trees have been called “poor man’s stained glass.”

People do notice the quality of bottles, so TricorBraun worked closely with American Glass Research (AGR), a leading consultant to the glass packaging industry since 1927 to verify ‘Acceptable Quality Levels,” also called AQL’s, to meet the industry standards, according to Suzanne Gordon, TricorBraun’s sales manager.

In regard to AQL inspection criteria, Petraitis said, ‘Every glass manufacturer that we deal with has their own AQL’s and defect classifications. If one of our customers has their own AQL, we can see if the manufacturer will comply. Some will and some will not. If the AQL’s are tighter, the glass will come with a higher price.”

After the inspection process, each bottle is sent on rollers or conveyor belts to be packaged in cartons, cases and pallets. The entire process can take anywhere from 36 to 48 hours, depending on the furnace pull.

According to Petraitis, ‘If there are different colors added to the furnace it can take 5 to 14 days to make the gradual change, depending on the color, while keeping the furnace level within 1/100 of an inch.”

For example, if the furnace is running green claret bottles and a change must be made to run clear flint bottles, the glass plant is required to slowly dump all colored glass raw materials out of the furnace. This gradual change over 5-14 days is necessary to keep the glass homogeneous enough to produce high quality bottles.

Plus, if the bottle size changes, the entire line can be down four hours to make the switch molds and another four hours to get back above 60% productivity.

‘Due to this long complex process, its essential that all wineries, small or large, get their bottle orders in as soon as they can,” Fenton said. “It takes so long to switch between colors and the need to change molds to run different bottle styles, therefore glass factories will often have a production plan mapped out months ahead of time.”

The cost of bottles is directly dependent on the cost of labor, which can be as much as 33%-40% of the total wine bottle cost. Some glass manufacturing has moved to Asia, Taiwan and Korea, where labor is 10% cheaper than the U.S. Other factors in the cost of glass bottles are the current price of raw materials and energy, whether it be coal, oil or electricity. Freight costs also factor into bottles prices.

Wine bottles have been part of the wine drinking experience since Roman times. It’s very likely that wine served in bottles will be the norm for future generations also.

This article was sponsored by TricorBraun WinePak, providing superior quality wine bottles, closures, capsules and services to the wine industry since 1982. Please visit their website at www.tricorbraunwinepak.com