Nitrogen and Its Importance in Fermentation Management

Winemaking begins in the vineyard, and so does nitrogen. Nitrogen is one of the most common elements in the universe. On Earth, in its elemental form, it exists as a gas that forms 80% of our atmosphere.

However, it is also a chemical constituent of many important components essential to life. Nitrogen makes up the building blocks of DNA, and it is also an important element in the composition of amino acids. When linked together, amino acids form the enzymes that drive all of life’s biochemical reactions. They are the building blocks to all proteins, hormones, and some plant metabolites that are responsible for wine flavor.

Plants draw mineral nitrogen from the soil and convert it to amino acids and other compounds. Animals who consume plants, in turn, ingest the nitrogen that the plants have drawn from the soil. Even single-cell organisms, such as yeast, need nitrogen for survival.

Many of us are well aware of the effects of nitrogen on the growth of plants. Nitrogen is the most important nutrient involved in regulating vine growth, morphology, and tissue composition. Soils that are high in nitrogen cause an increase in vigor, which can lead to shaded canopies and high yields of unripe fruit in vineyards. However, it is also important to understand how the nitrogen that is in fruit at harvest can have an effect on fermentation.

What’s your YAN, man? When grapes or other fruits are harvested, they contain nitrogen in many different chemical forms. The most important nitrogen-containing compounds for fermentation are free amino acids (FAN), ammonium ions (NH3), and small peptides. These compounds can, for the most part, be consumed by yeast during fermentation and are collectively called yeast assimilable nitrogen, or YAN.

What’s your YAN, man? When grapes or other fruits are harvested, they contain nitrogen in many different chemical forms. The most important nitrogen-containing compounds for fermentation are free amino acids (FAN), ammonium ions (NH3), and small peptides. These compounds can, for the most part, be consumed by yeast during fermentation and are collectively called yeast assimilable nitrogen, or YAN.

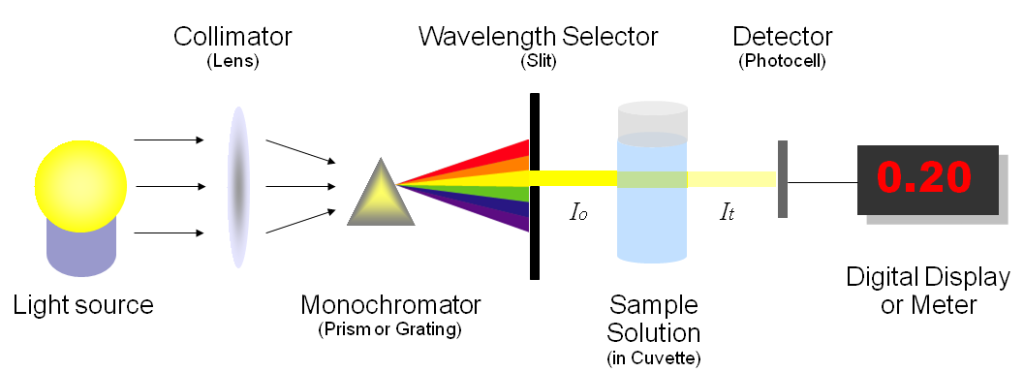

The free amino acid content (FAN) of the grape juice can be measured by a variety of different methods, but the most commonly accepted way to measure it is the NOPA assay. I won’t detail the procedure here as there are plenty of resources available, but it is worth noting that a spectrophotometer is needed in order to interpret the results. For wineries looking to upgrade their lab, I’d highly recommend investing in this piece of equipment.

The ammonia (NH3) content of juice (which is 83% nitrogen) is measured enzymatically, and the results are also determined by a spectrophotometer. The sum of the FAN and the NH3 collectively give us the amount of YAN in the juice.

Another method for measuring YAN is called the Formol titration method. While it is a simpler method, involving only a titration, it does involve using a Formaldehyde solution. In order to mitigate health and safety risks with this method, the titration must be performed under a fume hood — which is a much greater investment for a winery than the cost of a spectrophotometer. Newer methods of measuring YAN are also available, but require highly specialized lab equipment.

How a Spectrophotometer Works

Nitrogen and fermentation. After sugar, nitrogen is the most important macronutrient for yeast. When juice is lacking in nitrogen, the yeast can exhibit sluggish fermentations, create off-odors, and eventually expire before consuming all the sugar resulting in stuck fermentations.

Yet, while every winemaker I know carefully tracks the ºBrix (sugar) in their fruit, many winemakers don’t always measure the nitrogen content of the juice. Why? Well, many simply add a set amount of nitrogen (in the form of commercial yeast nutrients) as part of their regular fermentation protocol. Or, perhaps they don’t add a standard addition at the start of fermentation, but as soon as the wine starts smelling ‘stinky” (sulfide aromas like cooked cabbage or rotten eggs), they add nitrogen in the form of salts such as diammonium phosphate (DAP).

When yeasts lack amino acids in their diet, they start to synthesize their own. Unfortunately, yeasts’ recipe for amino acids includes adding a bit of sulfur to create cysteine and methionene. When they then metabolize these amino acids, hydrogen sulfide is a byproduct.

Nonetheless, although a minimum amount of nitrogen is important to preventing fermentation difficulties, it is possible to have too much of a good thing. When the nitrogen concentration in the grape must is too high (>450-500 mg/L YAN), it can stimulate the yeast to start overproducing undesirable aroma compounds such as ethyl acetate – an acetate ester with a nail polish aroma.

Acetic acid production is also increased, as well as other aroma compounds that can be both beneficial and/or detrimental to a wine’s character. Even more disconcerting is the fact that wines made from high nitrogen juice contain greater amounts of the possibly carcinogenic compound ethyl carbamate.

Bacteria can transform any excess amino acids following fermentation into biogenic amines like histamine and phenylethylamine — compounds which can cause headaches, nausea, or extreme reactions such as heart palpitations and shortness of breath in those who are sensitive. Thus, knowing the quantity of nitrogen at the start of fermentation can help prevent some of the undesirable consequences of adding more nitrogen than necessary (not to mention the added cost of using these nutrients!).

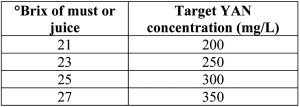

How much YAN do I need? The minimum amount of YAN needed for fermentation depends on a variety of factors such as the initial sugar concentration of the must, the fermentation temperature, and the strain of yeast used to ferment the wine. Nonetheless, it is generally accepted that juice with YAN less than 140-160 mg/L should be supplemented. Recommendations for initial YAN based on Brix levels have also been reported and used with success (table 1). Winemakers wishing for a fruitier style wine may wish to adjust their YAN to 300-350 mg/L, as at this level the maximum production of fruity ester aromas is obtained. YAN levels above 450-500 mg/L can lead to the production of off-aromas and flavors.

Table 1 – Recommended YAN concentrations as a function of sugar concentration

YAN and Cold-Hardy Hybrids. In general, University of Minnesota-developed hybrids contain high quantities of YAN, though variations in total YAN concentration can be seen depending on the geographic area of the vineyard. A recent survey of YAN in cold-hardy grape cultivars across the Eastern US conducted by Amanda Stewart as part of her phD dissertation at Purdue University found that 19 of the 20 highest reported YAN values were for University of Minnesota-developed cultivars. In fact, the highest ever reported YAN value for grapes (938 mg/L) was recorded in Frontenac Gris grown in Iowa. Her study also confirmed that YAN is highly variable and dependent not only on grape cultivar, but also by geographic location and vintage. This is confirmed by YAN data compiled at the Horticulture Research Center in Excelsior, MN. We have found YAN to be highly variable in Minnesota grapes. Because it is impossible to predict YAN concentrations, even from fruit grown in the same vineyard, it is recommended that winemakers always have their YAN quantified by a reputable lab prior to addition of any yeast nutrients.

Katie Cook is the enology project leader at the University of Minnesota. This article first appeared in ‘Notes from the North” which is published by The Minnesota Grape Growers Association and is reprinted with permission. For more information about the MGGA see: Minnesota Grape Growers Association

Ugliano, M., P. Henschke, M. Herderich, I.A. Pretorius. 2007. Nitrogen Management is critical for wine flavor and style. Australian Wine Research Institute. Wine Industry Journal. (22)6: 24-30.

Bisson, L.F., C.E. Butzke. 2000. Diagnosis and rectification of stuck and sluggish fermentations. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 51:168-177.

Stewart, Amanda. 2013. Nitrogen composition of interspecific hybrid and Vitis vinifera wine grapes from the Eastern United States. Doctoral Dissertation. Retrieved from Proquest Dissertations and Theses (Accession order No. AAI3592130)

1 Response

[…] Nitrogen and Its Importance in Fermentation Management […]