Fungicide-Resistant Downy Mildew Detected in Kentucky Vineyard

This summer, a grape grower in central Kentucky reported persistent downy mildew in his vineyard. He noted that regular applications of Abound and Pristine fungicides failed to manage the disease. After laboratory analysis, the pathogen was deemed completely resistant to the two fungicides at the lowest recommended rates and 85% resistant at the highest recommended rates.

What is fungicide resistance?

In the simplest terms, pathogens become resistant to fungicides when the chemical no longer manages disease symptoms. However, even the most effective fungicides fail to completely eradicate a pathogen population. There are always a few fungal spores or other fungal inoculum that survive the pesticide application. Those survivors may be the result of ineffective spray coverage, but individual pathogens may have a trait that provides some type of

resistance to the fungicide. Think back to high school biology when we learned the theory of ‘survival of the fittest.” Unfortunately, a single survivor can multiply into thousands of individuals while passing that resistance gene onto its offspring, much the way our parents passed on eye color to us.

How does resistance develop?

Consider that it is highly unlikely that a fungal population will incur resistance to more than one chemical type, at least over the short term. As a fungal population can become resistant to a single chemical, growers should rotate sprays with a different chemical group. These chemical rotations can become confusing, and many growers do not fully understand the concept of chemical groups.

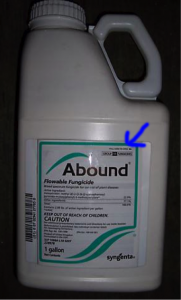

Chemical groups are classified by biochemical mode of action, not necessarily by active ingredient. For example, within the strobilurin group of fungicides, active ingredients include azoxystrobin, pyraclostrobin, trifloxystrobin, and kresoxim-methyl, all of which are quinone-outside inhibitors. Because information on biochemical modes of action can be confusing for growers, the Fungicide Resistance Action Committee (FRAC) developed numeric codes that represent these chemical groups. Strobilurins are classified as FRAC group 11. These codes appear on the top right side of all pesticide labels. Thus, growers may simply refer to the coded chemical group number on labels as opposed to depending upon complex information such as mode of action.

Considering that all fungicides within the same group have the same mode of action, it is clear that if a grower fails to properly rotate fungicide groups, fungicide resistance risk is high. Additionally, fungicide labels indicate the maximum number of applications allowed per growing season. A maximum of four applications of strobilurins are allowed per growing season. The grower mentioned above used Abound and Pristine fungicides consistently over a two-year period, exceeding the maximum number of applications and failing to rotate with a different chemical group. This rapidly induced the development of a resistant population of the downy mildew pathogen.

Fig 1. Abound fungicide is classified as a FRAC Group 11 fungicide. The chemical group code appears on the top right corner of fungicide labels

How does a grower know if a resistant population developed?

Pathogen populations do not begin as 100% resistant. In fact, resistance develops gradually. Thus, growers should be aware of efficacy and disease control. If a product(s) begins to become less effective over time, he should contact his local Extension agent immediately.

What next?

If resistant pathogen populations develop within a vineyard, growers should immediately stop using the fungicide in question and all others in the same FRAC group. With the assistance with an Extension agent or specialist, growers should identify other fungicides that will effectively manage disease. In the aforementioned case, the grower stopped using strobilurin fungicides and substituted a phosphorous acid fungicide (ProPhyt, Rampart, etc.) for management of downy mildew. If strobilurins are used for management of other diseases, tank-mix with another product (within a different FRAC group) that provides downy mildew control.

More Information

Fungicide resistance can appear complicated, so growers should not hesitate to seek assistance in development of a spray program. Contact the University of Kentucky (UK) Cooperative Extension agents or your local specialists for assistance.

Dr. Nicole Ward is a University of Kentucky Extension Plant Pathologist based in Lexington, Kentucky

[wp_geo_map]