How Do Midwest Consumers Define Local Wine?

Cheryl Nakata, a professor of marketing at The University of Illinois at Chicago Business School recently released an insightful study about about Midwest wine. From August 2014 through March 2015, Cheryl and Erin Peregrine Antalis, also of the University of Illinois at Chicago, interviewed owners and managers of fourteen wineries in Michigan and Indiana. The purpose of the study was to understand how the concept of ‘local” is interpreted by Midwest wine producers and consumers, and the value that the concept generates for wine products.

According to the study, The Midwest is experiencing a new appreciation of all things local, as reflected in the local food movement. That movement is fueled by consumers who want and do buy locally produced food, such as Michigan cherries and Wisconsin butter, sometimes sourced within a 100-mile radius; these ‘locavores” as they are called are propelled by the perception that food grown or made nearby is of higher quality and freshness, and the belief that buying it, even at premium prices, supports local farmers, businesses, and economy.

Nakata found that making estate grown wines is a goal for many Midwest wine producers. “As one winemaker noted, ‘What we are trying to do is produce high quality wine from fruit grown only from here and give people a sense of what this place tastes like in a wine glass.”

Nonetheless, since producers generally make some, perhaps most, of their wine from grapes not cultivated on their property, localness tends to be interpreted at higher or broader levels.

So long as the wine is made or ‘crafted” in the area, the claim of localness is made. Some winemakers do not blend and bottle all their wines, but have other producers in the area assemble them. Thus the notion of local is quite malleable and mutable, though state regulations govern what can be claimed on the bottle label.

For example, wines that are said to be a product of Michigan must contain 75% of Michigan grown grapes.

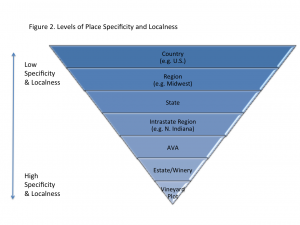

Varying interpretations of local in terms of place specificity leads to tension among winemakers to assert their interpretation over others and to be viewed as making the ‘most local” wines. Winemakers with more restricted interpretations of local are frustrated with winemakers who assume more liberal views.

For example, if a winemaker grows the majority of fruit on his or her estate and makes wine from that fruit, s/he defines the wine as local. That same individual would reject as genuinely local another winery’s products made from most or all fruit sourced outside of the AVA or state, even if crafted and bottled at the winery. The latter winery, however, would stress the location of the winemaking activities as what makes its wine local.

The sourcing of grapes is arguably the step that most signifies localness, as captured by a Michigan wine industry spokesperson: ‘Michigan’s distinction is that we make a very high percentage of our wine from grapes grown in the state. Not 100%, but it’s very high. Michigan wineries are very proud of the fact that they can label their wines with a Michigan appellation or AVA. In some Midwestern states, there are wineries that buy bulk wine from the West coast and bottle it in their home state. Serious wine consumers are looking for great wine produced from regionally grown grapes.” Others we interviewed argue that it’s the quality of grapes or juice–regardless of the source–that makes for distinctive and preferable wines.

Winemakers are also very interested in building their brands, whether the brand refers to their company name as applied on every bottle of wine or to specific lines within their product portfolios with unique names. As with all elements of localness already discussed, there is great divergence in the degree to and way in which localness is conveyed through brands.

For some wine producers, the brand is the place, as indicated by the name literally being where the winery is located. There is no mistaking where the product is made or at least sold from. For others, the brand name does not capture the specific location but rather the area’s positive essence. For example, the Leelanau Peninsula has beautiful harbors and beaches as well as a relaxed summer lifestyle, so a brand name may conjure images of these appealing spots and experiences. On the other end of the spectrum are brands that deliberately disassociate from the locale given the lack of advantage and perhaps even disadvantage from connecting with the region of origin. The following exchange reflects this thinking:

Interviewer: ‘Are you telling them [consumers] it’s a regional wine?”

Producer: ‘No. It’s just wine….We’re telling them it’s a brand….I’m not there to sell them an Indiana bottle of sweet fruity wine. I’m there to sell them a bottle of sweet fruity wine. The “Indiana” is not a component in our marketing.”

Arguably the winery is the most potent means of conveying localness in the marketing toolkit. The chief reason is the winery is a place. As a physical site, it carries with it a message that the wine is made right there, whether that is entirely the case or not. It is what consumers who walk into a winery and the tasting room assume. The sense of ‘this is where it all happens” generates excitement, and tethers the wine and the experience with the location. It also permits charging and obtaining more for a bottle of wine than typical in a grocery store or third party retailing site. People are paying for the experience of being where the wine is made and sampling it.

Expectedly, wine producers vary in their use of the winery to emphasize locality, but more engage in that use and find ways of heightening rather than diminishing locality through the winery. Some of the ways they heighten locality is to have a vineyard on the property in view of visitors, even if less than an acre; decorate the interior with photos or artwork of the area’s charms; provide places on the property for visitors to linger and enjoy scenic views, such as a porch for picnicking and wine sipping; give tours of the winemaking facilities and interesting yet non-intimidating tastings of wines; offer other products made nearby, such as local cheese and sausages; and present attractions that draw visitors, including live music, tasting events, wine education seminars, wedding and banquet services, cooking competitions, and even distilleries and breweries for those who don’t care for wine. All of these efforts provide opportunities for visitors to ‘consume” the place, not just the wine.

Hickory Ridge Winery in Southern Illinois is an example of a Midwest winery that closely associates grape production with the tasting room experience.

While producers are keenly aware of where their grapes come from as well as other markers of localness, consumers are far less informed and interested. Consumers instead focus on drinking and enjoying the wine at the winery, which makes the product local.

Seeing a vineyard on the property elevates that experience, as they assume the grapes are picked from that plot of land and squeezed into the bottle in front of them, whether or not that is accurate. Consumers are not very curious about the particulars of wine making, such as how soil type lends character to the wine. The concept of terroir bypasses most. Interest holds only to the degree the information adds to rather than detracts from the drinking and tasting experience. Two wine producers reflected on this situation:

‘They [consumers] don’t even understand ‘estate,’ that estate means that the grapes are all grown here and the wine is all made here. It’s hard to even get that across. It’ just going over their head. They’re like ‘Oh.’ Because I mean if you’re coming to a winery you think that the wine’s made there. That’s not always the case.”

‘But the consumer doesn’t [know some of our grapes are sourced out of state]. We tell people, but they don’t make that distinction. As far as they’re concerned, we’re a funky little winery…. The fact that some of our wines come from Northern California grapes or Southern Michigan grapes or from here, that doesn’t mean anything to them. They’re like ‘I’m here. I’m drinking, and I’m in the building. It’s local.'”

One manager explained how important the winery is in attracting visitors and providing an experience of place:

‘The winery is the number one ranked Trip Advisor location, so that’s just an example of what I mean. Like the truest experience here, the physical experience of being here, the place, is as important to that claim as the wine.”

Producers note that visitors in the area are on a vacation or travelling through, and stop at a winery unintentionally directed by road signs or intentionally on the quest for a local experience. In either case, the winery can provide a memorable and enjoyable time drinking wines in the company of others. Visitors later recall those moments as special when they are enjoying a bottle from that winery back home and reliving those times. One producer explained that he strove to deliver this experience, so customers would return to his winery and seek out his product at stores:

‘…most of it happens in the mind of the consumer, but the taste and the smell should, will provide linkages in their brain to like, ‘Oh, yeah. You know that was our, remember the picnic we had.’ [They] remember whatever that’s connected with their time in this place [the winery]…it’s about experience, building, giving them [consumers] an experience that they can remember whether they consciously do or you know. ‘Oh,…I had fun with that!’ It’s got to be a pleasurable experience.”

Nakata’s study concluded with several recommendations for Midwest wineries:

- Embrace the fluidity of the concept ‘local”

For consumers, local can mean anything from the product being cultivated locally, crafted locally, or sold locally. Local can also fluidly mean the immediate geographic location, such as a designated AVA, state, or region. While winemakers have their own interpretations of local, when pitted against the customers’, sales occur if what the producers offer meshes with customer desires. Frustration occurs otherwise, as shared by one producer, ‘People will go into a supermarket and buy something that says local without even looking at the label to see if it actually is local! I mean, they don’t’ care if it is made down the street or down state.” Nevertheless such frustrations signal an opportunity to redefine local in ways that are accessible to customers, capture a broader sense of regionality and place, and create or solidify connections to the regional wine experience.

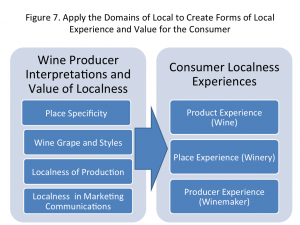

- Apply the four domains of local to create three forms of local experience and value for the consumer

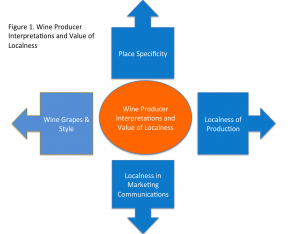

Producers interpret localness in terms of four domains: place specificity, wine grapes and styles, production localness, and marketing communications localness.

However, since consumers interpret localness in terms of experiences, it is important for producers to translate their four domains into the three localness experiences valued by consumers: product experience (wine), place experience (winery), and producer experience (winemaker relations.) Producers have wide latitude to design and insert localness into these experiences, and by so doing creatively elevate the value of the wine product and tighten bonds with customers. Important in this process, as implied by the above recommendation, is lowering demands that customers appreciate some of the nuances involved, such as the wine’s expression of terroir, unless particular customers are interested.

- Widen the notion of quality products to encompass sweet wines

A primary barrier to growth cited by wine makers is the negative image of Midwest wines. The notion that wine from the Midwest cannot be good persists. The root of this perception is the association of sweeter style wines with poorer quality. Yet this situation presents an opportunity to define a regional style that is positive and characteristic of the Midwest.

Rather than mimic established wine styles such as dry Californian or Pacific Northwestern styles, Midwest winemakers can carve out a unique regional niche by appealing to the significant segment of wine drinkers in the Midwest (and nationally) who have a sweeter palate.

Importantly, the quality of these wines would be emphasized, to break the association of sweetness with inferiority. Consumers who like sweet wines experience embarrassment, guilt, and shame when asking for sweet wines and consequently avoid wine. This largely unaddressed market could be offered wines suited to their palate instead of wines they are supposed to like. Overtime, the reputation of Midwest wines can grow, building cultural capital for these and other regional products.

- Intentionally target Millennials and Generation X’ers

The Millennial and Generation X cohorts present attractive segments for Midwest wine producers. As younger and less experienced wine drinkers, they are more open to the styles, varieties, including hybrid grapes, and blends offered in the Midwest. Without highly fixed preferences and expectations, they approach wines as uncharted territory and embrace those they like. Millennials in particular adopt wines, drinking more than previous generations (Nowak, Thach, and Olsen 2006). To target intentionally means to carefully create the three experiences with these groups in mind, and especially in the tasting room, where the first and most potent experience occurs. Twenty to thirty year olds place the highest value on experience, and so it is critical to ensure that the initial encounter with the wine, winery, and winemaker (or representative) is very positive.

Cheryl Nakata is a Professor of Marketing at The University of Illinois at Chicago. She has a PhD from UIC and a BA with honors in English from the University of Hawaii. For more information see: Cheryl’s webpage.