Would You Like A State Funded Wine Organization?

The state funded wine organizations, like those in Missouri, Indiana and Michigan, can be a tremendous boost to their local wine industries because of the marketing help and education they can provide to winemakers. Irv Geary and the MGGA contacted Midwest Wine Press and asked if we could investigate the structure and funding of the wine boards or councils in these three states, to help with the MGGA’s own discussions about whether to pursue establishing a similar organization in Minnesota.

See related article: Report on State Wine Orgs Presented at Cold Climate Conference

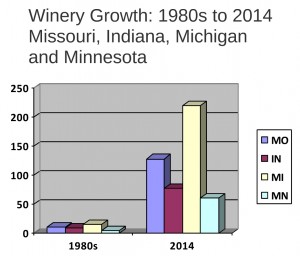

While it may seem self-evident, as far as I could tell, there really isn’t any concrete research that says, ‘If your state has a publicly funded wine organization, your wine industry will grow.” When you compare the growth in the Minnesota industry alongside Indiana and Missouri, the industry up in the colder north has really done well without a publicly funded organization to help (probably a tribute to the hard work of the MGGA). On a graph which shows winery numbers in the 1980s (when MO’s, IN’s and MI’s state orgs were all founded) for Missouri, Indiana and Minnesota compared to now, you wouldn’t necessarily pick out Minnesota as the state without a publicly funded wine organization. Minnesota has grown pretty well without one. However, Michigan’s growth over that time has been the most explosive — up from perhaps about thirty wineries in the mid-1980s to more than 220 now. Was that due to its state funded wine organization or other factors? These are the questions to tussle with when you look into the impact of state wine organizations!

However, away from the research, just talking to winemakers, you get the message that they really appreciate the marketing help and education that a state wine organization with stable funding can provide. The difficulty for a state wine organization is deciding how to do that. That may sound obvious, but it is worth considering that our wine industry across the Midwest is so diverse. Is there another wine industry in the world that has such a mix of winery business models? We have wineries that are more like wedding centers, wineries that don’t grow any grapes, wineries where it’s all about the tasting room experience, wineries that import a lot of fruit, wineries that only use local fruit. Are they all wineries? Do you try and help everyone? In which case, not everyone is interested in making quality wine — so should that be your focus? I think the answer is yes and state wine organizations shouldn’t be afraid about emphasizing that their key role is establishing a local wine industry based on wineries that make wine from locally grown, preferably estate grown grapes. But, perhaps one problem state wine organizations have is trying to keep everyone happy.

The aim and general focus of the publicly funded state wine organizations in Missouri, Indiana and Michigan are very similar. In short, to promote a quality local wine industry in their state by educating winemakers about growing grapes and winemaking and then helping to spread the word about their product by marketing it to consumers.

However, there are differences in these states when you look at the structure of their governing boards and their funding mechanisms.

For example, Missouri’s board is heavily tipped towards wineries: eight of the eleven members are from wineries and the biggest three wineries in the state: St James, Les Bourgeois and Stone Hill are all represented on the board.

Indiana’s council is bigger with 20 members and actually has more from wineries on it than Missouri: 12, but that is balanced by 7 representatives from Purdue University.

Then Michigan’s board of 12 is more evenly distributed with wineries, government bodies and the alcohol industry sharing much of the power.

But where does the power really lie on these boards? I came away from this research feeling that the structure of these boards tell one side of the story, the other side is the personalities on them. So without having actually observed any of their meetings, it is quite hard to jump to firm conclusions about how they come to decisions and who dominates that process.

The funding mechanisms are also different. Missouri’s Grape and Wine Fund pulls in $1.8 million per year from the 12 cents per gallon it gets whenever a gallon of any wine is sold in the state. Indiana’s fund is based on the same mechanism but it doesn’t get as much: 5 cents per gallon of wine sold that brings in a budget of about $500,000. Michigan’s funding mechanism is completely different and comes from more than a thousand alcohol related businesses that pay what’s called a non-retail liquor license. The funding brings in about $750,000.

Indiana’s funding situation is tight and Michigan would probably prefer to have the per gallon tax instead — so Missouri has it best in the funding stakes.

One interesting issue for me as a journalist, was the level of transparency of these publicly funded organizations. While all of them have websites listing wineries, wine trails, events and their general aims and structure as organizations, finding more than just very general budget details or more detailed information on issues discussed at meetings was tough in the cases of Missouri and Indiana. In fact, I came away surprised at how unwilling or unable these states were to be open about their budgets, not just to me as a journalist, but so the public who are their paymasters, can see where their money is going. Michigan was the exception in this regard — an up to date and detailed annual budget can be found on its website and fairly up to date minutes of board meetings.

There’s an argument that says greater transparency would help accountability and also improve the way tasks are planned and carried out. Again, I felt Michigan was a better performer in terms of articulating its goals and what it does, both to me in interviews, and via its website — perhaps this is a direct result of its budget transparency.

Finally, one big issue for local wineries is getting their wine to market. One criticism of state funded wine organizations is that they don’t do enough to directly help small winemakers in this regard and in fact may just encourage a status quo that keeps the three tier system of alcohol sales and distribution in place — a system that doesn’t help the little guys. The response from some state wine organizations is that they can’t get involved in politics. Again, Michigan plays its hand wisely in this regard: it doesn’t get involved in politics but it does talk about its role as an educator. It’s a fine line, but small winemakers in emerging wine regions like the Midwest need state wine organizations that are willing to push the envelope in terms of getting local wine beyond the tasting room and into restaurants and liquor stores.

This article originally appeared in the Spring edition of the MGGA’s quarterly newsletter, ‘Notes from the North’, volume 41, issue 1.